Uncategorized

A complete history of roller skating in Sydney

Sydney’s love affair with roller skating is a story of boom, bust, and revival spanning nearly 150 years. From Victorian-era rinking halls filled with well-dressed colonials gliding under gaslight, to the neon-lit roller discos of the 1980s, roller skating has repeatedly captured the city’s imagination. This in-depth history traces the evolution of roller skating in Sydney – a journey through social fads, technological changes, and community spirit – and highlights why this nostalgic pastime is again rolling back into popularity.

Early Beginnings in the 19th Century

Roller skates themselves date back to the 18th century (the first recorded use was in 1743 in London), but it wasn’t until the late 19th century that Sydney saw its first taste of the new craze. By the 1870s, roller skating had been introduced to Australia and was becoming a popular pastime in Sydney, with some of the earliest rinks opening during that decade[2]. These initial venues were modest, but they set the stage for a much larger roller-skating boom to come.

The 1880s “Rinking” Craze

Sydney truly caught roller skating fever in the mid-1880s. The period between 1885 and 1890 saw an explosion of skating venues – at least 25 roller-skating rinks opened across the city. This sudden mania was so widespread it earned its own nickname: “rinking.” Entrepreneurs rushed to build lavish rinks, hoping to cash in on the trend. The rinks weren’t just recreation spots; they became grand social halls where Victorian Sydneysiders mingled and showed off their skating prowess.

One of the most spectacular was the Darlinghurst Skating Rink, which opened with great fanfare in May 1889. A crowd of about 2,000 people gathered for its inaugural night – an astonishing turnout that underscored skating’s popularity. Spanning a colossal 350 feet in length by 130 feet in width, the Darlinghurst rink was touted as the “largest rink in the world,” and the Sydney Morning Herald proclaimed it the “largest and best fitted skating rink in the Southern Hemisphere” at the time. Newspapers described the opening as “the social event of the season,” with fashionable ladies and gentlemen in attendance and a military band playing from a suspended bandstand. Skaters gliding under electric arc lights and multicolored gas lanterns could even see their reflections in giant wall mirrors – a thrilling novelty in the 1880s.

“The finest roller skating rink in the colony.”

– The Sydney Morning Herald, April 5, 1889

Several other rinks vied for supremacy during this boom. Notable venues included the Elite Skating Rink in Surry Hills (near Prince Alfred Park), the Redfern Palace Skating Rink on Cleveland Street, the Crystal Palace Rink on York Street, and Newtown’s famed Trocadero. Each tried to outdo the others in size and attractions. At the Trocadero in Newtown – a state-of-the-art rink commissioned by entrepreneur Frederick Ferrier – the Sydney Morning Herald marveled at its grand opening in April 1889, calling it “the finest roller skating rink in the colony”. This Newtown Trocadero boasted an immense column-free skating floor and even an innovative retractable roof for ventilation, illustrating how much investment and engineering went into these pleasure palaces.

Professional skating stars also arrived to capitalize on the craze. The period’s most celebrated performer was American trick skater Robert J. Aginton, dubbed the “King of the Rink.” Aginton toured Australian rinks demonstrating jaw-dropping stunts – from racing down steep ramps to spinning in place at 300 revolutions per minute – all while exuding showmanship and bravado. Newspapers of the day reported that he earned up to £100 per week for his skating exhibitions – a hefty sum in the 1880s – reflecting just how much drawing power these spectacles had. With entertainers like Aginton on the bill, nightly sessions were as much theatrical performances as they were sporting events.

The atmosphere at Sydney’s rinks during the “rinking” craze was electric yet surprisingly orderly. One account noted that even with the vast crowds at Darlinghurst, there was “not a sign of larrikinism or rough play” – novices and experts alike skated with a sense of decorum. Masquerade nights became a popular highlight: skaters dressed in elaborate costumes for carnival-like “fancy dress” sessions on the rink. Prizes were awarded for the best-dressed or best skating couples, prompting participants to don outfits ranging from angels and butterflies to playful impersonations of newspapers and cabbages. These festive events kept the public coming back and generated extensive press coverage, further fueling the skating fad.

It’s worth noting that this era left an intriguing legacy: Australia’s earliest surviving film footage, shot in 1896, features a roller skater performing outdoors in Sydney’s Prince Alfred Park. The short film Patineur Grotesque (by Marius Sestier of the Lumière brothers) captures a prankish roller-skater in action. At the time, Prince Alfred Park itself had no rink, so the skater may have been a professional practicing or entertaining Exhibition Building visitors. The film and the many newspaper reports from the 1880s underscore how deeply skating had embedded itself in Sydney’s popular culture by the end of the 19th century.

End of an era: The 1890s Decline

As feverish as Sydney’s roller craze was, it proved short-lived. By the early 1890s the novelty began to wane, and attendance dipped. The economic depression of 1893 delivered a severe blow to leisure industries; purse strings tightened, and many skating entrepreneurs found their businesses no longer sustainable. One by one, rinks that had been packed only a few years earlier started closing their doors.

Sydney’s magnificent Trocadero in Newtown – opened in 1889 at the height of the boom – shut down as a skating rink by 1893 amid the economic downturn. Other rinks met similar fates. By the mid-1890s, the great “rinking” boom of Sydney was effectively over, ending its first chapter in the city’s history. Roller skating didn’t disappear entirely (a few die-hards and amusement halls kept it flickering on), but it would be nearly a decade before the sport returned to vogue.

Edwardian Revival: Skating’s Golden Years (1900s–1910s)

At the turn of the 20th century, roller skating in Sydney staged a remarkable comeback. By 1904–1905, entrepreneurs were once again opening rinks and the public was rediscovering the joy of eight wheels on wood flooring. In fact, some venues from the 1880s were reborn – literally in the case of the Newtown Trocadero, which was refurbished and reopened as Williams’ Skating Rink and Music Hall in 1903. This time around, operators paired skating with other entertainments (like live music, billiards or cafés) to broaden the appeal.

Sydney in the Edwardian era saw roller skating become downright fashionable again. By the early 1910s the city was dotted with rinks new and old, drawing in a whole new generation of skaters. The monumental Exhibition Building at Prince Alfred Park (originally built for expos in the 1870s) was even converted into a public roller skating rink in 1904, giving central Sydney a large skating venue once more (it remained a rink until a war memorial was later installed on the site). In the eastern suburbs, the Centennial Skating Palace at Bondi Junction (opened in 1906) became one of the most popular rinks of this era. Suburban areas weren’t left out either – neighborhoods from Redfern to Petersham had their local rinks or skating clubs by 1910.

Interior of the Centennial Skating Rink in Bondi Junction, photographed circa 1934. The Centennial (also called Centennial Skating Palace) hosted not only public skating sessions but also roller hockey matches, dances, and community events. In 1913 it was advertised as “the largest roller rink in Australia” and promoted as “the fashionable winter pastime” at “Sydney’s most popular rink”.

By 1913, roller skating was at a peak of popularity nationwide. Those who didn’t skate themselves could be entertained by watching professional performers: that year the famous skating duo Nellie Donegan and Earle Reynolds toured Australian theatres, performing graceful dance routines on roller skates to delighted audiences. Sydney’s rinks, meanwhile, bustled nightly with patrons. Newspapers noted that competition between rival skating rinks was fierce – each venue tried to offer something unique to attract crowds.

Some rinks focused on sport: organized roller hockey leagues formed, and matches were held to the cheers of spectators. (In fact, world speed skating records were even set on Sydney roller rinks during this time, underscoring the serious athletic side of the activity.) Other rinks emphasized theatrical flair: costume carnivals, “fancy dress” skate nights, and novelty races became common. An “Eastern Exotic Gala” might be on the program one week, followed by comic wheelbarrow or sack races on skates the next. Every rink had its own flavor. At the Imperial Roller Rink in Sydney, the floor manager became locally famous for an eccentric party trick – upon request, he would perform his “imitation of an albatross in flight” while skating around flapping his arms. Such quirky amusements gave each rink a distinct character.

“…skate and be graceful, skate and enjoy yourself as you have never done before.”

– Robert J. Aginton, champion skater, 1909

This Edwardian skating renaissance firmly reestablished roller skating as a favorite Sydney pastime. Skating was seen as a wholesome, family-friendly form of recreation and exercise – one that was accessible to both sexes and all ages (many rinks offered free instruction to beginners, and daytime sessions were held for children). By the eve of the First World War, Sydneyites were once again “rinking” with enthusiasm, just as their parents had in the 1880s. Unbeknownst to them, the coming war and social changes would soon pause the party once more.

War and Aftermath

World War I (1914–1918) interrupted Sydney’s skating scene. As young men went to war and austerity measures took hold at home, leisure activities like roller skating inevitably slowed down. Some rinks were repurposed for the war effort – for example, Newtown’s Trocadero building was used as a community relief center for soldiers’ families during 1916–1922. Other halls turned into makeshift drill rooms, donation centers or were simply shuttered due to lack of patrons. By the end of the war, a number of pre-war rinks had closed, and the roller skating craze cooled during the 1920s as Australians embraced new entertainments (like the cinema, radio and jazz dancing).

Yet, even through the quieter 1920s, skating did not vanish entirely. A few stalwart rinks hung on, operating as multi-purpose venues. For example, some dance halls would occasionally clear the floor for roller skating nights. This set the stage for the next resurgence. By the end of the 1920s and into the 1930s – ironically, as the Great Depression hit – roller skating in Sydney was poised to roll back into fashion yet again.

The Great Depression Revival (1930s)

Perhaps surprisingly, the 1930s brought another wave of roller skating popularity in Sydney. Around 1930, the pastime “took off as a hobby” once more, as if following a roughly 20-year cycle of resurgence. Several factors contributed to this revival. The economic hardship of the Depression era meant people sought affordable escapism and social activities close to home. Roller skating, with its relatively low cost (after a one-time skate purchase or a small rental fee), fit the bill perfectly for many. Additionally, entrepreneurs found a new opportunity in repurposing old venues – notably, many disused picture theatres (cinemas) were converted into skating rinks around this time as talking movies and radio had dented cinema attendance.

A prime example of this trend was Parramatta’s Rivoli Rink. In 1930, the old Star cinema in Church Street, Parramatta was transformed into a roller skating arena and renamed The Rivoli[31]. The owners laid a new maple skating floor at great expense and launched the venue with much publicity. The response was tremendous: on one July 1930 evening, over 1,000 people packed into the Rivoli for a special skating carnival, turning the rink into a “virtual fairyland” of whirling couples in glittering costumes. The local press marveled at the sight of “hundreds of skaters in kaleidoscopic fancy dress” under the lights. Roller hockey also made a comeback – the Rivoli even formed its own team and in May 1930 hosted the first game of a new inter-rink hockey competition against the Centennial Skating Rink from Bondi, winning 2–1. Clearly, the public’s appetite for skating and associated sports was back.

Other suburbs saw similar developments. Bondi’s Centennial Skating Palace (which had thrived pre-war) continued as a major hub, advertising itself in 1933 as “Sydney’s most popular rink.” North of the harbor, rinks in Manly and Chatswood drew weekend crowds. Even smaller towns around NSW dusted off their skates – local newspapers from 1931–1935 are filled with notices of skating club nights and competitions. The community aspect of roller skating was strongly evident in the 1930s: churches, youth groups and councils organized skating parties as morale-boosting events during tough economic times.

By the late 1930s, roller skating had cemented itself once again as a beloved recreational activity in Sydney’s social life. This era’s enthusiasm even survived into the early years of World War II – but as the war intensified, most rinks either closed or were converted to support the war effort (as had happened in WWI). For instance, Parramatta’s Rivoli was requisitioned by the military in 1942 as an army depot, abruptly ending its skating days (it would reopen after the war as a dance hall rather than a rink). Likewise, many 1930s rinks did not return to skating after WWII. Sydney’s roller skating scene would lie relatively dormant for some time, awaiting the next generation.

Mid-Century Challenges and Changes (1940s–1960s)

The mid-20th century was a quieter period for roller skating in Sydney. The 1940s and 1950s saw the rise of new cultural phenomena – rock’n’roll music, television, and the automobile – which provided alternative forms of entertainment and leisure. As a result, roller skating waned in popularity and many of the grand rinks from earlier decades either shut down or reinvented themselves. For example, the Parramatta Rivoli never returned to skating; it became a full-time ballroom and community hall in the 1950s. The famous Centennial Roller Rink at Bondi was eventually demolished (its exact closure date is unclear, but it no longer operated as a rink by the post-war years). Other pre-war rinks were repurposed into cinemas, dance halls, or simply fell victim to urban redevelopment.

And yet, the embers of Sydney’s skating culture did not extinguish completely. In the early 1960s, Australia experienced a modest roller skating revival once again. This coincided with a wave of nostalgia for the big-band era and renewed interest in social dancing – skating rinks began to double as dance venues, and vice versa. Entrepreneurs, noting that many suburban picture palaces were closing due to television’s popularity, decided to convert some of those spaces into new skating rinks. In Sydney, several old cinemas in suburbs like Homebush and Five Dock were converted into roller rinks during the early 1960s. These new rinks were smaller and more modest than the Victorian behemoths, but they provided local youth a place to hang out and have fun on skates.

At the same time, some new purpose-built rinks opened on Sydney’s fringes. Oral histories mention a roller rink at Hurlstone Park and another at Liverpool operating in the 1960s. While the scale of skating’s popularity in the ’60s never matched the frenzy of the 1880s or 1910s, it did foster a dedicated community of skaters and set the stage for what was to come. By the end of the 1960s, roller skating was poised for perhaps its most iconic era – one that would forever link it with disco beats and flashy fashion.

The Roller Disco Era (1970s–1980s)

The 1970s ushered in the golden age of roller disco, a pop-culture phenomenon that swept Sydney along with the rest of the world. Several innovations sparked this boom. Crucially, the invention of the polyurethane wheel (around 1970) made roller skates faster, smoother, and more maneuverable than the old metal or wooden wheels. Suddenly, skaters could dance and perform tricks with unprecedented ease. This advancement dovetailed perfectly with the burgeoning disco music scene of the mid-70s – and a match made in heaven was born.

By the late 1970s, roller skating rinks transformed into neon-lit discotheques on wheels. In Sydney, as in New York or Los Angeles, teenagers and young adults flocked to rinks on Friday and Saturday nights to groove under mirror balls and strobe lights, all while on skates. “Roller disco was all the rage on the dancefloors of the glitzy ’70s and ’80s,” as one retrospective noted. The atmosphere at these roller discos was exuberant and colorful: DJs pumped out the latest hits by the Bee Gees or Madonna, skaters wore fashion as loud as the music (think neon leg warmers, short-shorts, sequined outfits), and the venues themselves glowed with blacklights and arcade-game marquees. Rinks became social hotspots where you might skate a few laps, play a round of Pac-Man at the adjoining arcade, and share a milkshake with friends at the snack bar – all in one night out.

Sydney had its share of famous roller disco spots. In the western suburbs, the St. Marys “Saints” Roller Rink(later renamed Wheelies) was legendary for its lively sessions in the early 1980s. In Campbelltown, a large rink known as Skateways (or Campbelltown Rollerdrome) drew crowds of youths every weekend, to the extent that it was “the place to be” for local teenagers in the ’80s. The northern suburbs and beaches were not left out either – rinks in Brookvale and Dee Why attracted throngs of skaters, while an outdoor roller rink at Sefton made news as well. Even the inner city saw a resurgence: a roller skating center in Petersham and sessions at venues in Balmain and Marrickville popped up during the craze.

The roller disco boom also permeated broader culture. Television shows featured skaters in variety acts; pop stars held roller-themed parties; and movies like Xanadu (1980) glamorized the art of dancing on skates. Sydney hosted competitive artistic skating and speed skating events in this era as well, though the focus had shifted more to recreational fun. It seemed for a few years that everyone either had a pair of skates or knew someone who did.

Yet as the calendar turned to the mid-1980s, the fad component of roller disco began to fade. Tastes in music and entertainment changed (the rise of video games and MTV, for example, offered new diversions). Attendance at rinks dipped, and one by one many of Sydney’s roller discos began to close. By the mid to late 1980s, the roller skating craze “lost its mojo,” as observers put it. Some stalwart rinks tried to soldier on into the early ’90s by rebranding or adding new attractions (like inline skating, which became popular in the 1990s), but most couldn’t survive the downturn. The great roller discos of Sydney fell silent, and another chapter of skating history came to an end.

Decline and Modern Resurgence (1990s–Present)

The 1990s were a tough decade for roller skating in Sydney. With the ’80s fad over, many rinks shut their doors permanently. As one longtime skater lamented, “my local rink closed in the 1990s and never reopened.” In fact, most of the dedicated roller rinks across Australia closed over the past few decades, and Sydney was no exception. By the early 2000s, the city that once boasted dozens of rinks had very few left. Iconic venues like the Blacktown Indoor Rink or Penrith’s Emu Plains Skatel either closed or struggled to attract new generations raised on different pastimes. The era of large, ubiquitous skating palaces appeared to be over.

However, even during these quiet years, a core community of skaters kept the spirit alive. Inline skating (rollerblading) became a popular fitness trend in the 1990s, and Sydney’s smooth coastal promenades – such as the path from Manly to Dee Why – often teemed with inline skaters, hinting that the love of wheels on feet was merely taking a new form. By the 2000s, roller derby leagues began to emerge, reintroducing old-school quad skating to a new audience, particularly young women. The formation of teams like Sydney Roller Derby(founded in 2007) tapped into the DIY, punk-infused revival of roller skating as a contact sport. Roller derby’s growth through the 2010s proved that skating could thrive even without traditional rinks; games took place in community halls or sports centers, drawing enthusiastic crowds and creating a vibrant subculture.

In recent years, there has been a clear retro revival of roller skating in Sydney, echoing a global trend. By 2018, media reports were noting that roller skating was “making a comeback” as people rediscovered its nostalgic fun[49]. Part of this resurgence has come from pop-up events and portable rinks. For example, lifelong skaters like John Harvey have toured regional New South Wales with mobile roller rink setups, bringing the joy of skating to festivals and small towns that haven’t seen a rink in decades[50][49]. At the same time, organizations such as RollerFit (founded in Sydney) have sprung up to offer classes and social skating sessions in rented venues. RollerFit’s success – hosting regular learn-to-skate classes for adults and kids at community centers in Tempe, Alexandria, and other parts of Sydney – underscores that there is still a passionate appetite for skating, even without permanent rinks.

Meanwhile, social media and fashion have played a role in the renaissance. Vintage-style quad skates have become a trendy accessory, and videos of graceful skaters dancing in parks to retro music have gone viral, inspiring new folks to lace up skates. During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, this trend accelerated worldwide as many sought outdoor exercise and nostalgic hobbies; Sydney was no different, with local retailers selling out of skates and more skaters seen cruising along beachside paths.

Today, roller skating in Sydney is emphatically back on a roll – albeit in a different form than the giant rinks of yesteryear. You’re as likely now to find skaters at a “rink on wheels” pop-up in a parking lot, at a themed disco night in a multi-use hall, or simply improvising a skating dance party under a harborside pavilion. The community is tight-knit and creative, making do with limited infrastructure. From artistic dance skaters and fitness enthusiasts to roller hockey players and derby competitors, they all share a common lineage that traces back to those 19th-century pioneers.

Preserving the Legacy: Why Sydney Needs SKTNG Again

Looking over this long history, one notices a cycle: each time roller skating seemed to fade away, Sydney found a way to revive it. This resilience speaks to an enduring appeal of skating – it’s exercise, art, and social connection all rolled into one. Yet, unlike past eras, modern Sydney currently lacks a large, dedicated roller skating venue in the city. Enthusiasts often have to travel far, skate outdoors, or rely on temporary set-ups.

Advocates argue that there is a real need for “SKTNG” (roller skating) facilities in Sydney today, both to honor the city’s rich skating heritage and to meet contemporary demand. The recent grassroots revival shows that people, young and old, are eager to glide on eight wheels if given the opportunity. A new permanent skating center – or a network of community rinks – could provide a safe, inclusive space for this growing community, much like the rinks of bygone days did. It would also keep alive the traditions and skills passed down through generations of Sydney skaters.

In conclusion, the story of roller skating in Sydney is more than just nostalgia; it’s a reminder that this pastime has woven itself into the social fabric of the city time and again. From the Victorian rinking aristocrats, to the roaring crowd at a 1930s carnival, to the disco divas under the mirrorball, to today’s revivalists teaching each other moves in a carpark – skating has a magical way of bringing people together in joy. As Sydney looks to the future, investing in skating (or “SKTNG”) could ignite that magic for a new era, ensuring that the city’s roller skating legacy keeps on rolling.

How movement builds real connection

Why Sydney Needs SKTNG More Than Ever

In an age where “connection” usually means Wi-Fi, the simple act of being in a room together — skating, laughing, moving — feels quietly revolutionary. If you've been searching for something more real, something that gets you off the scroll and into a shared moment with actual people, you're not alone.

SKTNG isn't just another roller skating rink in Sydney. It’s a community in motion. A rebellion against the algorithm. A place where the lights are low, the music can be loud, and the people are fully present. This I suppose you could call a 'movement movement' — and it's just getting started.

The truth is, we’re drowning in convenience. Our catch-ups have become group chats. Our shared experiences are livestreamed. Movement has been replaced by marathon scroll sessions, and attention spans are fraying fast. Over 60% of Australians say they feel less connected now than before the pandemic — and it's not just the kids. Families, creatives, freelancers, even retirees are feeling it. We weren’t designed for this much screen time. We were made for movement, for laughter, for community that actually shows up.

Roller skating brings all of that back. It’s not just nostalgic — it’s social fitness. It lifts your mood, builds confidence, and surrounds you with people who are doing the same. When you're on skates, you're in sync with others — moving, reacting, playing, falling, laughing. You might come to SKTNG alone, but you'll leave having nodded, smiled, or skated past someone who made your day just a little brighter.

Science backs it up. Movement boosts serotonin and dopamine, the chemicals that help you feel good and build trust. Group activity lowers stress and enhances belonging. Add music into the mix and you’ve got an emotional cocktail that no social media app can replicate. There’s a reason we feel so good after skating: it reminds us we’re alive, connected, and capable of joy without a screen in sight.

And the research doesn’t stop there. Multiple studies have shown that roller skating is one of the most effective full-body, low-impact exercises. It improves cardiovascular health, balance, flexibility, and coordination, all without the strain of high-impact sports. But it’s not just physical. The World Health Organization reports that regular physical activity like skating can reduce the risk of depression by up to 30%, while improving memory, sleep quality, and emotional regulation.

For kids and teens, skating enhances focus, reduces anxiety, and supports social development. For adults, it’s a powerful antidote to work stress and digital burnout. For older skaters, it promotes joint mobility, balance, and cognitive health — helping prevent falls and even slow memory loss. Few activities support wellness this holistically, and fewer still do it with music, laughter, and four wheels under your feet.

SKTNG is our way of giving Sydney something it desperately needs — a third space. Not home. Not work. A space that doesn’t require a booking, a purchase, or a perfect outfit. It’s a cultural home for anyone who wants to just be. Whether you’re a teen tired of TikTok, a parent craving something fresh and screen-free, or someone who simply wants to feel part of something again — this is for you.

The rink is the anchor, but it’s only the beginning. At SKTNG, you’ll find music, themed nights, social skating games, community events, and more. The energy is electric, but inclusive. You're not expected to be good — you're just encouraged to show up. It’s about presence, not performance. And that starts the moment you lock your phone away and step onto the floor.

Because here’s the thing: we’re not anti-tech. We just believe some moments are better without the filter. Eye contact. Shared laughter. The feeling of rolling side by side with someone to a song you forgot you loved. These moments don't need to be posted — they need to be felt. That’s what SKTNG is here for.

We’re designing every inch of the space with people in mind, not profiles. A rink with proper maple flooring. Lighting that makes you feel something. Sound systems that thump just right. And a vibe that invites everyone in. It’s not about content — it’s about connection.

Whether you're new to skating or haven’t put on skates since the 90s, you’re welcome here. Come for the fun, stay for the movement, and leave with a clearer head and maybe a few new mates. No filters. No feeds. Just freedom — the way it used to feel before everything got so curated.

Follow @SKTNG.space or SKTNG.space on facebook

The movement is real. And it’s rolling soon.

No filters. No feed. Just freedom.

Why the future needs third spaces

It’s time to lace up, unplug, and roll into something real.

Remember when you could just be somewhere?

No expectations. No agenda other than to hang out, move your body, and bump into friends or total strangers — and maybe leave with a story or two.

Those places are disappearing. Fast.

In today’s cities, we’ve got two main destinations: home and work. And if you’re lucky, you might have a favorite café, a friend’s place, or the odd pub where you can gather. But the middle ground — what sociologist Ray Oldenburg called the “third place” — is vanishing. And with it, we’re losing something vital: the simple joy of human connection.

What Is a Third Space, Anyway?

Third spaces are the public or semi-public spots where community thrives. They’re not home (first space) and they’re not work (second space). They’re where life happens in between. Think: old-school roller rinks, some gyms, churches, rec centers, corner stores, skate parks, youth clubs, even record shops or video arcades.

They’re where you go just to be — no bouncer, no reservation. Just music, laughter, shared time, and maybe a few bad dance moves.

But with rising rents, shrinking leisure zones, and the algorithm slowly swallowing our downtime, these places are being replaced by feeds, not feelings.

Where Did All the Third Spaces Go?

Blame urban sprawl. Blame screens. Blame the fact that every square metre of public space now needs a business model. Or maybe blame the rise of “on-demand everything” culture. Regardless, here’s where we are:

Teen are loitering in shopping centres because there’s nowhere else to gather.

Friends catch up less in person, because why not just DM or send memes instead?

Families have fewer active, social spaces that aren’t sports fields or restaurants.

Loneliness has become a public health crisis, with social isolation affecting physical and mental health at every age.

We’re constantly online, but rarely with anyone.

Reclaiming Real Life (On Wheels)

Here’s the radical idea: What if we brought back the third space — but made it roll?

Enter: SKTNG.

SKTNG isn’t just a roller rink. It’s a movement — in more ways than one. It’s a vibrant, reimagined third space for everyone:

- Teens who need somewhere safe but fun

- Parents who want their kids off screens (and maybe even join them)

- Creatives and freelancers looking for a work-meets-play vibe

- Night owls who want more than just pubs and clubs

- Locals looking to feel like they belong somewhere again

- It’s a place you don’t need a reason to visit — you just go because it feels like yours.

Retro Wheels, Future Feels

Roller skating is having a major glow-up. The global roller skating market is booming, driven by everything from nostalgia to TikTok trends to a rediscovery of low-impact fitness. But more than that, it’s becoming a symbol of connection.

You can’t doom-scroll while skating.

You move together. Fall (yes, it happens to the best of us). Laugh. High-five strangers. You remember what real community feels like. It’s sweaty, it’s silly, it’s soul food.

And it doesn’t require a password or a profile pic.

The Future Rolls Here

We’re building SKTNG to be that rare, magic place:

- Where teens and toddlers and retirees can all share the same space.

- Where the lights glow, the music flows, and the Wi-Fi is intentionally weak.

- Where movement creates momentum, and people remember how to be people again.

Because the future doesn’t need more apps. It needs places.

Third places. Safe places. Real places. Places like SKTNG.

So roll in. Bring your friends. Or make some here.

Because you shouldn’t need a reason to belong somewhere.

Follow @SKTNG.space or SKTNG.space on facebook

The movement is real. And it’s rolling soon opening announcements, and community events.

Better yet — sign up to our mailing list and be first through the doors when the future arrives..

No AI. No algorithms. Just humans. #SKTNG

Roller skating as a rebellion against screens

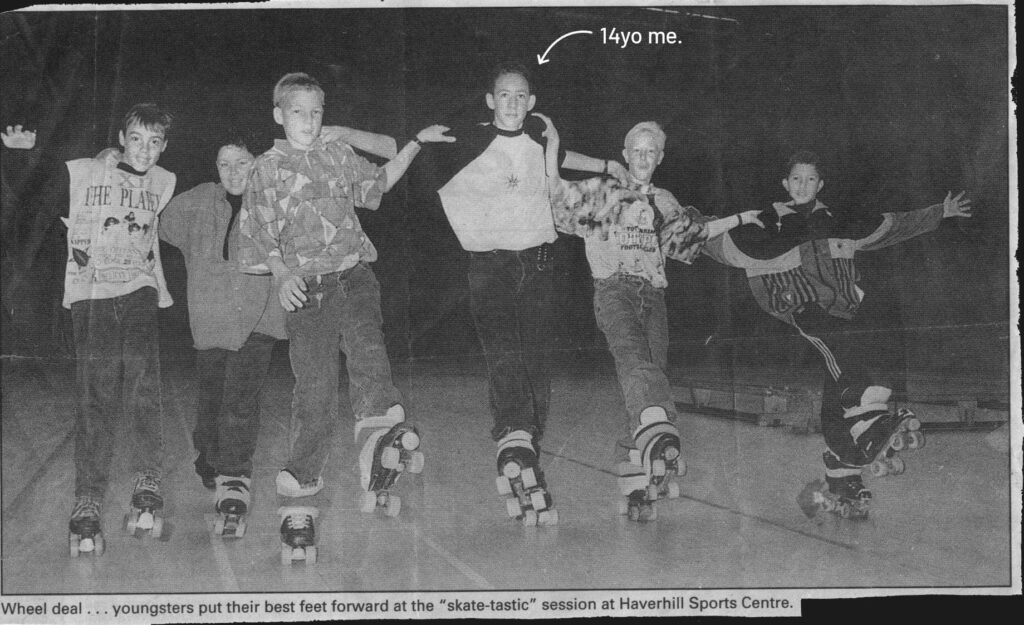

How my roller skating childhood inspired a movement for the future

I grew up in Haverhill, a small town in the UK, tucked in the corner of Suffolk on the border with Essex, and Cambridgeshire. With a population of ~20,000 people, it wasn’t exactly a bustling metropolis. But for me, it had everything, because I had friends that lived close, miles of paths to ride my bike and I could roller skate.

At age 13, I was roller skating every chance I got — bombing the slopes behind my house on a school driveway, doing laps of the empty school playground, skating in circles for hours with my Walkman in my pocket, headphones on, fully lost in the music and the movement. Those early sessions weren’t about performance or exercise — they were about freedom.

By 15, my parents were driving me 20 miles each weekend to our local rinks, Rollerbury in Bury St Edmunds or Rollerworld in Colchester. Both had 25m x 50m Olympic-grade maple rotunda roller skating floors, proper lighting rigs, massive sound systems, and DJs spinning everything from R&B, pop to dance tunes. The Prodigy played there, Take That!. Mr Blobby showed up once. I skated with strangers who became friends, and friends who became family.

By 16, I was roller skating at all-night sessions — the kind where you'd start skating at 10pm, blink and realise it’s 7am Sunday morning.

At 17, the first place I drove after passing my driving test? the rink.

And that crew? That massive crew I rolled with back then? Even when I moved to Australia — literally the other side of the world — I still keep in touch with almost all of them. Some of them still roller skate every week. That community never really left us.

Even though both of these iconic rinks have now been pulled down for developments, the culture, community and memories have lived on long past any physical buildings. But now, we catch up at different rinks, outside but still on skates.

From Playground Games to Push Notifications

Now fast-forward to 2025.

Kids aren’t bombing driveways anymore. They're not gliding around playgrounds with a Walkman and an imagination. They're inside. Sitting. Scrolling. Watching someone else have fun.

According to Common Sense Media, kids aged 8–12 average 5.5 hours of screen time a day. Teenagers average 8.5+ hours. That’s not including schoolwork — that’s pure, unfiltered scroll time.

It’s no wonder we’re seeing record highs in anxiety, depression, and disconnection in young people. They’re more “connected” than ever — yet they’re missing real connection.

Roller skating as Digital Defiance

Roller skating is more than movement — it’s medicine.

At SKTNG, we’re bringing back that wild, wonderful, real-life experience I grew up with. Not as a throwback. Not as a gimmick. But as a radical alternative to the endless feed.

Roller skating makes you feel alive. You’re in your body. You’re in the moment. You fall. Laugh (a lot). You get back up. Learn, not by clicking a video, but by trying — and failing — and trying again.

When you're skating, your phone isn't in your hand. It's in a locker. And your focus is on the here and now: the music, the rhythm, the people, the vibe.

Games, Chaos, and Community

We’re rebuilding the rink culture I grew up in — the one that shaped me, my friends, our community.

Where Sunday nights meant chaos and connection:

“Trains” — linking bodies and barrelling across the floor, the whips were legendary

“Little Man” (shooting the duck)— crouching low and weaving through packs of skaters

“Chariots” — two people sitting together, intertwined, someone pushes, and you fly

“British Bulldog” — full-contact roller mayhem, no pads, no helmets (don’t tell our insurance provider)

“The Dice Game, Speed Skating, Limbo, Last Man Standing” — it was glorious madness

It was play. It was adrenaline. It was belonging. And it was all without screens.

That’s what SKTNG is bringing back — a space where games, culture, and community collide, on wheels.

This is not nostalgia.

It’s resistance. Its presence. It’s the future we want—made of people, not programs.

In a world where everything is increasingly digitised, gamified, and monetised, the simple act of showing up, moving your body, and connecting with others in real time is revolutionary.

SKTNG is more than a roller rink. It’s a third space. A cultural hub. A digital detox zone. A place where kids, teens, families, creatives, misfits, and movers come together not to scroll — but to roll.

Join the Movement

We need more than likes. More than followers. We need friends, stories, shared experiences, and safe spaces to just be.

So whether you’re 7, 27, or 67 — whether you’ve never skated or you’ve still got your original wheels — come be part of something real.

Come skate. Connect. Rebel — with lights, music, and a little bit of wobble.

Follow @SKTNG.space or SKTNG.space on facebook

The movement is real. And it’s rolling soon.